This is an article I snatched from the New York Times…

What you don’t know is this: you teach your children to color inside the lines, never experiment, never make mistakes, to live in fear, and to experience little. To not even experience what they experience. To be little soldiers that will make you look good, while you attempt to live your life and give as little attention to the kids as you can.

Hell on earth…

One one hand you are protective, on the other you neglect them… And then you fell guilty.

Just look back at your childhood. You are stunted, and your children are stunted.

This article explains some of why… some, not all.

In the article of my own that I will publish today (it’s not ready yet) I will add some more clarity.

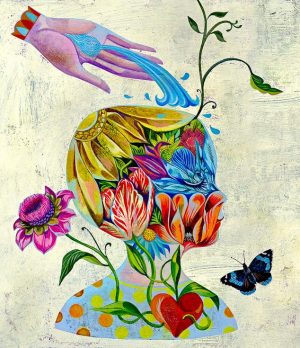

Caring for children shouldn’t be like carpentry, with a finished product in mind. We should grow our children, like gardeners

By Alison Gopnik

A strange thing happened to mothers and fathers and children at the end of the 20th century. It was called “parenting.” As long as there have been human beings, mothers and fathers and many others have taken special care of children. But the word “parenting” didn’t appear in the U.S. until 1958, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, and became common only in the 1970s.

People sometimes use “parenting” just to describe what parents actually do, but more often, especially now, “parenting” means something that parents should do. “To parent” is a goal-directed verb; it describes a job, a kind of work. The goal is to somehow turn your child into a better or happier or more successful adult—better than they would be otherwise, or (though we whisper this) better than the children next door. The right kind of “parenting” will produce the right kind of child, who in turn will become the right kind of adult.

The idea that parents can learn special techniques that will make their children turn out better is ubiquitous in middle-class America—so ubiquitous that it might seem obvious. But this prescriptive picture is fundamentally misguided. It’s the wrong way to understand how parents and children actually think and act, and it’s equally wrong as a vision of how they should think and act.

Taking care of children has always been a central, and difficult, human project. Our children depend on us for much longer than the children of any other animals. By the time they are 7, young chimpanzees gather as much food as they consume. Even in hunter-gatherer groups, human children don’t do that until they’re at least 15.

So you need lots of people to take care of human children, not just mothers but fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, uncles and aunts and siblings and cousins and even friends. Biologists have shown that humans evolved a unique network of care. Unlike our nearest primate relatives, extended family and “alloparents” (unrelated helpers) all combine to take care of those needy kids.

For most of human history, we lived in these extended family groups. This meant that we learned how to take care of children by practicing with our own little sisters and baby cousins and by watching many other people take care of children.

But toward the end of the 20th century, families got much smaller and more scattered, people had children later, and middle-class parents spent more time working and going to school. The traditional sources of wisdom and competence weren’t available any more.

Today, most middle-class parents spend years taking classes and pursuing careers before they have children. It’s not surprising, then, that going to school and working are modern parents’ models for taking care of children: You go to school and work with a goal in mind, and you can be taught to do better at school and work.

Working to achieve a particular outcome is a good model for many crucial human enterprises. It’s the right model for carpenters or writers or businessmen. You can judge whether you are a good carpenter or writer or CEO by the quality of your chairs, your books or your bottom line. In the “parenting” picture, a parent is a kind of carpenter; the goal, however, is not to produce a particular kind of product, like a chair, but a particular kind of person.

In work, expertise leads to success. The promise of “parenting” is that there is some set of techniques, some particular expertise, that parents could acquire that would help them accomplish the goal of shaping their children’s lives. And a sizable industry has emerged that promises to provide exactly that expertise. Some 60,000 books are in the parenting section on Amazon, and many of them have “how to” somewhere in the title.

The scientific study of development provides very little support for this picture. It’s true that childhood experiences can influence adult life: Children who are poor or neglected are more likely to have problems as adults, and enrolling those children in high-quality preschools makes their lives better later on.

But middle-class parents obsess about small variations in parenting techniques. Should you co-sleep with your babies or let them cry it out? Should strollers face front or back? How much homework should children have? How much time should they spend on the computer? There is almost no evidence that any of this has much predictable effect on what children will be like when they grow up.

Does this mean that parents don’t matter? To the contrary: From a scientific perspective, being a parent, as opposed to “parenting,” is crucially important, but it’s important in a very different way.

Why do we have such a long immaturity, such an extended childhood, with all the cost that entails? Our long human childhood (and the major investment in caring for children that goes with it) is one of the keys to human evolutionary success.

More than any other animal, we human beings depend on our ability to learn. And the current thinking is that our large brain and powerful learning abilities evolved, most of all, to deal with change.

The immediate trigger for human evolution seems to have been a period of unpredictable climate variability in the Pleistocene era. It wasn’t just that the weather got warmer or colder, but that it moved from one extreme to the other in an unpredictable way. Humans are causing climate change now, but in the evolutionary past, climate change caused humans.

On top of that, human beings were nomadic, moving from environment to environment, and, thanks to culture, each new generation could create and modify its own environment. All this meant that humans had to adapt to an exceptionally wide range of exceptionally variable environments.

One way that the human species may have evolved to deal with this variability was by nurturing a wide range of children with very different temperaments and abilities. This helped to ensure that someone or other in a new generation would have the skills to cope with the unpredictable and unforeseeable environments that they might face.

Human learning contributes even more to the variability of our children. Our parental investment and commitment allow each generation a chance to think up new ideas about how the world works and how to make it work better. Childhood provides a period of variability and possibility, exploration and innovation, learning and imagination.

Many animals have minds that are exquisitely adapted to just one particular environment. Our minds can change in unpredictable ways to match unpredictable environments. But this strategy has a drawback: You can’t simultaneously learn about a new environment and act on it effectively. You don’t want to be stuck figuring out how to deal with a mammoth while it’s charging at you.

The evolutionary solution to that trade-off is to give each new human being protectors—people who make sure that children have a chance to thrive, learn and imagine before they have to fend for themselves. Those protectors also pass on the knowledge that previous generations have accumulated.

If “parenting” is the wrong model, then, what’s the right one? Let’s recall that “parent” is not actually a verb, nor is it a form of work. What we need to talk about instead is “being a parent”—that is, caring for a child. To be a parent is to be part of a profound and unique human relationship, to engage in a particular kind of love, not to make a certain sort of thing.

After all, to be a wife is not to engage in “wifing,” to be a friend is not to “friend,” even on Facebook, and we don’t “child” our mothers and fathers. Yet these relationships are central to who we are. Any human being living a fully satisfied life is immersed in such social connections.

Talking about love, especially the love of parents for their children, may sound sentimental and mushy and simple and obvious. But like all human relationships, our love for our children is at once a part of the everyday texture of our lives and enormously complicated, variable and even paradoxical.

We can work to love better without thinking of love as a kind of work. We might say that we try hard to be a good wife or husband, or that it’s important to us to be a good friend or a better child.

But I wouldn’t evaluate the success of my marriage by measuring whether my husband’s character had improved in the years since we wed. I wouldn’t evaluate the quality of an old friendship by whether my friend was happier or more successful than when we first met. This, however, is the implicit standard of “parenting”—that your qualities as a parent can be, and even should be, judged by the child you create.

The most important rewards of being a parent aren’t your children’s grades and trophies—or even their graduations and weddings. They come from the moment-by-moment physical and psychological joy of being with this particular child, and in that child’s moment-by-moment joy in being with you.

Instead of valuing “parenting,” we should value “being a parent.” Instead of thinking about caring for children as a kind of work, aimed at producing smart or happy or successful adults, we should think of it as a kind of love. Love doesn’t have goals or benchmarks or blueprints, but it does have a purpose. Love’s purpose is not to shape our beloved’s destiny but to help them shape their own.

What should parents do? The scientific picture fits what we all know already, although knowing doesn’t make it any easier: We unconditionally commit to love and care for this particular child. We do this even though all children are different, all parents are different, and we have no idea beforehand what our child will be like. We try to give our children a strong sense of safety and stability. We do this even though the whole point of that safe base is to encourage children to take risks and have adventures. And we try to pass on our knowledge, wisdom and values to our children, even though we know that they will revise that knowledge, challenge that wisdom and reshape those values.

In fact, the very point of commitment, nurture and culture is to allow variation, risk and innovation. Even if we could precisely shape our children into particular adults, that would defeat the whole evolutionary purpose of childhood.

We follow our intuitions, muddle through and hope for the best.

Perhaps the best metaphor for understanding our distinctive relationship to children is an old one. Caring for children is like tending a garden, and being a parent is like being a gardener. When we garden, we work and sweat and we’re often up to our ears in manure. We do it to create a protected and nurturing space for plants to flourish.

As all gardeners know, nothing works out the way we planned. The greatest pleasures and triumphs, as well as disasters, are unexpected. There is a deeper reason behind this.

A good garden, like any good ecosystem, is dynamic, variable and resilient. Consider what it takes to create a meadow or a hedgerow or a cottage garden. The glory of a meadow is its messiness: The different grasses and flowers may flourish or perish as circumstances alter, and there is no guarantee that any individual plant will become the tallest, or fairest or most long-blooming. The good gardener works to create fertile soil that can sustain a whole ecosystem of different plants with different strengths and beauties—and with different weaknesses and difficulties, too.

Unlike a good chair, a good garden is constantly changing, as it adapts to the changing circumstances of the weather and the seasons. And in the long run, that kind of varied, flexible, complex, dynamic system will be more robust and adaptable than the most carefully tended hothouse bloom.

As individual parents and as a community, our job is not to shape our children’s minds; it is to let those minds explore all the possibilities that the world allows. Our job is not to make a particular kind of child but to provide a protected space of love, safety and stability in which children of many unpredictable kinds can flourish.

It’s not easy to be a parent, especially in the U.S. right now. It takes time and energy and money to provide the support and nurture that children need. We evolved in small-scale societies, where an extended group of caregivers could spontaneously provide resources for the children they loved. In a big, postindustrial world, we treat most human activities as if they were either a kind of production or a kind of consumption—so that raising children is seen as either very badly paid work or a very expensive kind of luxury.

But the “parenting” industry isn’t the answer. Instead, we have to find a way to help parents be parents, and to provide the love and care that all children deserve.

This essay is adapted from Dr. Gopnik’s “The Gardener and the Carpenter: What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us About the Relationship Between Parents and Children,” which will be published in early August by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. She is a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, and a regular contributor to Review’s “Mind & Matter” column.

Read the original article: A Manifesto Against ‘Parenting’