This week has been a success for Life, and a disaster financially. Everyone was spending their money on turkey, I guess.

This week has been a success for Life, and a disaster financially. Everyone was spending their money on turkey, I guess.

So I am going to announce some sales for this coming week. I’ll make them good… so you’ll buy.

Now, about the successes that lead me to a huge insight.

All that people do is guided by memes, and they think they decided to do it. And you think they decided to do it from the goodness of their heart, from the badness of their heart, whatever seem to be the case. But in fact they never decided anything… It is the memes that are doing the deciding.

This is a totally different way to look at people, at life, and at what’s happening.

You can use this to re-interpret your past.

My “Playground: it is never too late to have a happy childhood” was a program where we experimented with this, even though at the time there were no distinctions, like memes used in the work. I bet it would have been easier and faster.

Why? Because the moment you realize that no one ever says or does anything that is not coming from the memes, including your father, including you… it is easier to have compassion for the perpetrator, and it is easier to have compassion for yourself.

Why? Because the moment you realize that no one ever says or does anything that is not coming from the memes, including your father, including you… it is easier to have compassion for the perpetrator, and it is easier to have compassion for yourself.

This is a revolutionary way to look at life, but judging from the results, this is a way that returns the power to you.

Now, did you EVER have the power in your life?

The answer won’t surprise you because it matches your experience.

No, you never had the power. Why? Because you never had your own thinking not modified, colored, or directed by the memes. Family, peers, caretakers, teachers, clergymen, doctors… you never did your own thinking.

They gave you your words in full sentences… memes.

These memes tell you what you can, what you can’t, what you should do.

These memes tell you how the world is. How to tell if someone is a friend or a foe. They tell you want to do, how to do it… like a straitjacket.

Here is a fantastic article on this topic… from the New Yorker Magazine. Both fascinating and horrifying seeing the memes in action.

The Root of All Cruelty?

The Root of All Cruelty?

Perpetrators of violence, we’re told, dehumanize their victims. The truth is worse.

By Paul Bloom

Violent acts are often motivated, rather than countermanded, by ethical norms.

A recent episode of the dystopian television series “Black Mirror” begins with a soldier hunting down and killing hideous humanoids called roaches. It’s a standard science-fiction scenario, man against monster, but there’s a twist: it turns out that the soldier and his cohort have brain implants that make them see the faces and bodies of their targets as monstrous, to hear their pleas for mercy as noxious squeaks. When our hero’s implant fails, he discovers that he isn’t a brave defender of the human race—he’s a murderer of innocent people, part of a campaign to exterminate members of a despised group akin to the Jews of Europe in the nineteen-forties.

The philosopher David Livingstone Smith, commenting on this episode on social media, wondered whether its writer had read his book “Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others” (St. Martin’s). It’s a thoughtful and exhaustive exploration of human cruelty, and the episode perfectly captures its core idea: that acts such as genocide happen when one fails to appreciate the humanity of others.

One focus of Smith’s book is the attitudes of slave owners; the seventeenth-century missionary Morgan Godwyn observed that they believed the Negroes, “though in their Figure they carry some resemblances of Manhood, yet are indeed no Men” but, rather, “Creatures destitute of Souls, to be ranked among Brute Beasts, and treated accordingly.” Then there’s the Holocaust. Like many Jews my age, I was raised with stories of gas chambers, gruesome medical experiments, and mass graves—an evil that was explained as arising from the Nazis’ failure to see their victims as human. In the words of the psychologist Herbert C. Kelman, “The inhibitions against murdering fellow human beings are generally so strong that the victims must be deprived of their human status if systematic killing is to proceed in a smooth and orderly fashion.” The Nazis used bureaucratic euphemisms such as “transfer” and “selection” to sanitize different forms of murder.

As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss noted, “humankind ceases at the border of the tribe, of the linguistic group, even sometimes of the village.” Today, the phenomenon seems inescapable. Google your favorite despised human group—Jews, blacks, Arabs, gays, and so on—along with words like “vermin,” “roaches,” or “animals,” and it will all come spilling out. Some of this rhetoric is seen as inappropriate for mainstream discourse. But wait long enough and you’ll hear the word “animals” used even by respectable people, referring to terrorists, or to Israelis or Palestinians, or to undocumented immigrants, or to deporters of undocumented immigrants. Such rhetoric shows up in the speech of white supremacists—but also when the rest of us talk about white supremacists.

It’s not just a matter of words. At Auschwitz, the Nazis tattooed numbers on their prisoners’ arms. Throughout history, people have believed that it was acceptable to own humans, and there were explicit debates in which scholars and politicians mulled over whether certain groups (such as blacks and Native Americans) were “natural slaves.” Even in the past century, there were human zoos, where Africans were put in enclosures for Europeans to gawk at.

Early psychological research on dehumanization looked at what made the Nazis different from the rest of us. But psychologists now talk about the ubiquity of dehumanization. Nick Haslam, at the University of Melbourne, and Steve Loughnan, at the University of Edinburgh, provide a list of examples, including some painfully mundane ones: “Outraged members of the public call sex offenders animals. Psychopaths treat victims merely as means to their vicious ends. The poor are mocked as libidinous dolts. Passersby look through homeless people as if they were transparent obstacles. Dementia sufferers are represented in the media as shuffling zombies.”

The thesis that viewing others as objects or animals enables our very worst conduct would seem to explain a great deal. Yet there’s reason to think that it’s almost the opposite of the truth.

At some European soccer games, fans make monkey noises at African players and throw bananas at them. Describing Africans as monkeys is a common racist trope, and might seem like yet another example of dehumanization. But plainly these fans don’t really think the players are monkeys; the whole point of their behavior is to disorient and humiliate. To believe that such taunts are effective is to assume that their targets would be ashamed to be thought of that way—which implies that, at some level, you think of them as people after all.

Consider what happened after Hitler annexed Austria, in 1938. Timothy Snyder offers a haunting description in “Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning”:

The next morning the “scrubbing parties” began. Members of the Austrian SA, working from lists, from personal knowledge, and from the knowledge of passersby, identified Jews and forced them to kneel and clean the streets with brushes. This was a ritual humiliation. Jews, often doctors and lawyers or other professionals, were suddenly on their knees performing menial labor in front of jeering crowds. Ernest P. remembered the spectacle of the “scrubbing parties” as “amusement for the Austrian population.” A journalist described “the fluffy Viennese blondes, fighting one another to get closer to the elevating spectacle of the ashen-faced Jewish surgeon on hands and knees before a half-dozen young hooligans with Swastika armlets and dog-whips.” Meanwhile, Jewish girls were sexually abused, and older Jewish men were forced to perform public physical exercise.

The Jews who were forced to scrub the streets—not to mention those subjected to far worse degradations—were not thought of as lacking human emotions. Indeed, if the Jews had been thought to be indifferent to their treatment, there would have been nothing to watch here; the crowd had gathered because it wanted to see them suffer. The logic of such brutality is the logic of metaphor: to assert a likeness between two different things holds power only in the light of that difference. The sadism of treating human beings like vermin lies precisely in the recognition that they are not.

What about violence more generally? Some evolutionary psychologists and economists explain assault, rape, and murder as rational actions, benefitting the perpetrator or the perpetrator’s genes. No doubt some violence—and a reputation for being willing and able to engage in violence—can serve a useful purpose, particularly in more brutal environments. On the other hand, much violent behavior can be seen as evidence of a loss of control. It’s Criminology 101 that many crimes are committed under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and that people who assault, rape, and murder show less impulse control in other aspects of their lives as well. In the heat of passion, the moral enormity of the violent action loses its purchase.

But “Virtuous Violence: Hurting and Killing to Create, Sustain, End, and Honor Social Relationships” (Cambridge), by the anthropologist Alan Fiske and the psychologist Tage Rai, argues that these standard accounts often have it backward. In many instances, violence is neither a cold-blooded solution to a problem nor a failure of inhibition; most of all, it doesn’t entail a blindness to moral considerations. On the contrary, morality is often a motivating force: “People are impelled to violence when they feel that to regulate certain social relationships, imposing suffering or death is necessary, natural, legitimate, desirable, condoned, admired, and ethically gratifying.” Obvious examples include suicide bombings, honor killings, and the torture of prisoners during war, but Fiske and Rai extend the list to gang fights and violence toward intimate partners. For Fiske and Rai, actions like these often reflect the desire to do the right thing, to exact just vengeance, or to teach someone a lesson. There’s a profound continuity between such acts and the punishments that—in the name of requital, deterrence, or discipline—the criminal-justice system lawfully imposes. Moral violence, whether reflected in legal sanctions, the killing of enemy soldiers in war, or punishing someone for an ethical transgression, is motivated by the recognition that its victim is a moral agent, someone fully human.

In the fiercely argued and timely study “Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny” (Oxford), the philosopher Kate Manne makes a consonant argument about sexual violence. “The idea of rapists as monsters exonerates by caricature,” she writes, urging us to recognize “the banality of misogyny,” the disturbing possibility that “people may know full well that those they treat in brutally degrading and inhuman ways are fellow human beings, underneath a more or less thin veneer of false consciousness.”

Manne is arguing against a weighty and well-established school of thought. Catharine A. MacKinnon has posed the question: “When will women be human?”

Continue reading on the New Yorker’s site

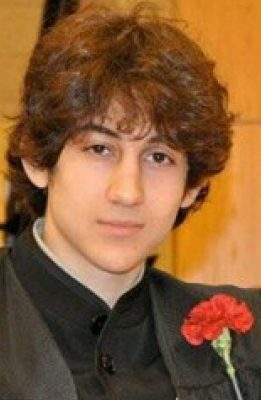

Feeling Sorry for Tsarnaev

Feeling Sorry for Tsarnaev

By Paul Bloom

May 16, 2013

In my article in the magazine this week, I made the case against empathy. Our capacity to put ourselves in the shoes of others—to feel their pain, to make their goals our own—might well be essential for intimate relationships. Nobody would deny that parents should feel empathy toward their children, or that romantic love requires the bond that empathy provides. But when we use empathy as a guide to policy, it often takes us in irrational and cruel directions.

This is particularly clear when we look at the criminal-justice system. People are understandably empathetic toward the victims of crime, particularly when they are young and vulnerable, when they are attractive, and when they share our race or ethnicity. It is far harder to empathize with those who are accused or convicted of these crimes. Rather, we want these individuals to suffer. Some would argue that this is a properly moral reaction, but this retributive impulse can motivate legal and policy decisions that many see as unjust, such as three-strikes laws, harsh mandatory sentences, and the mass incarceration of racial minorities.

Sometimes, though, empathy has a quite different effect. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is accused of setting bombs in Boston that killed three people, including an eight-year-old boy, and that maimed many others. He seems like the perfect villain. But in a blog post on Slate, Hanna Rosin writes about the warmth and compassion directed toward Tsarnaev by certain teen-age girls and, weirdly, by mothers: “In the past week and a half I have not been to a school pickup, birthday, book party, or dinner where one of my mom friends has not said some version of ‘I feel sorry for that poor kid.’ ”

Rosin explores different explanations for this reaction, suggesting that it stems from how Tsarnaev was initially described—“a hapless genial pothead being coerced into killing by his sadistic older brother.” But she later settles on an account which I believe is both unsettling and correct: “Dzhokhar is cute.” In a recent discussion with Robert Wright, the law professor and blogger Ann Althouse makes a similar point, commenting, sarcastically, on the media coverage: “Look at this Boston bombing. The pictures of those two brothers. Aren’t they cute?”

Psychologists have long observed the importance given to the face. The most striking demonstration I know of has to do with how competent one looks. The psychologist Alexander Todorov and his colleagues showed people black-and-white headshots of the winners and runner-ups in elections for various House and Senate races. After ensuring that their subjects were unfamiliar with the politicians, the psychologists simply asked: Who looks more competent? Over two thirds of the time, subjects selected the photo of the winning candidate.

Read the whole article on the New Yorker’s site

Read the original article: Want to be the one who is making the decisions in your life?